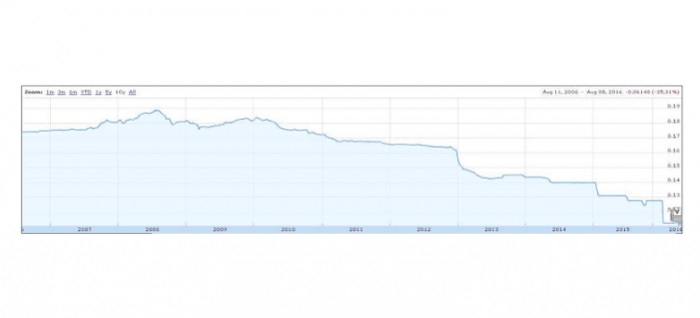

On Monday, July 25, the Egyptian pound (LE) reached its lowest value ever in the parallel market. The unofficial exchange rate, LE12.95 per U.S. dollar, was a staggering 47% below the government-set rate of LE8.88 to the dollar.

The accelerating decline of the Egyptian economy has brought unprecedented public scrutiny of economic conditions, with citizens increasingly feeling the pinch. In May 2016, headline urban inflation increased by an annual equivalent of 12.3%, the highest monthly figure since May 2015. More worryingly, this inflation was led by basics needs: food and health expenditures.

This scrutiny, however, also amplifies crises, and with the exchange rate crisis on everyone’s mind, it is a spiraling self-fulfilling prophecy, fueled by short term mismanagement and long-term economic decline.

In 2015, Egypt allowed the currency to depreciate three times by a combined 8.7%. In March 2016, a further 13% depreciation—the largest in 13 years—brought the exchange rate to LE8.95 per dollar, on hopes that this would be sufficiently close to the currency’s real price to regain investor confidence, quell the parallel market, and replenish the country’s foreign currency reserves. This was to be supported by a more flexible exchange rate which would allow for fractional daily variations of the exchange rate. Withdrawal restrictions were eased, and it seemed, for a brief moment, that the worst of the crisis had passed. But the Central Bank of Egypt (CBE) never reviewed its exchange rate policy. Instead, it reverted to a currency peg which allowed for little fluctuation, while it continued to allocate dollars to banks. The trend of depreciation, if only on the black market, resumed.

A number of short-term factors, exacerbated by a background of overall economic decline and currency and capital flight, accelerated the crisis over the past week. Deliberate speculation and hoarding—in addition to a self-fulfilling market panic, where investors and consumers demand more than their actual needs for fear of not finding dollars when they need them in the future—explain part of the problem . The central bank’s mismanagement in this crisis is inexcusable, with the governor of the CBE regularly suggesting in interviews that the currency will be devalued, apparently forgetting the power of such declaration to affect faith in the currency and thus exchange rates.

On July 3, CBE Governor Tarek Amer told financial newspaper al-Mal in a phone interview that he was not targeting the dollar-pound exchange rate, and that maintaining the exchange rate was a “huge mistake” that had cost the country billions of dollars over the past five years. Amer added that the central bank had received loans and deposits to the tune of $22.5 billion over that same period, most of which was wasted on exchange rate targeting, and “which should have been used to fix the monetary policy and the forex system.”

While his mea culpa was correct, the statement’s timing immediately before the Eid al-Fitr long weekend set the market into a frenzy, on the expectation that the CBE would devalue the currency immediately after the holiday. But the bank did not devaluate, and the black market rate kept climbing.

The CBE further fueled the panic by imposing currency withdrawal restrictions to laughable sums, with the customers of some banks reporting that their withdrawal quota while abroad decreased by 90%, from $5,000 to $500 per month. Such restrictions are instrumental in encouraging informal transactions, as consumers turn to the black market to fund their currency needs for travel or purchases.

On July 20, Amer said that the time was not ripe to float the currency, but left the door open for further devaluations, which only fueled the frenzy further. Pinning the entirety of the crisis on the CBE’s performance over the course July would be unfair. Its mismanagement goes back further than the past few weeks, long predating the mandate of the current CBE governor. It is, however, essential to underline his mismanagement of the crisis.

The general economic context has not made this easy. Devaluations usually entail imported inflation—price increases for imported goods and domestic products relying on imported raw materials—and in a country with no consumer protection regulation to speak of, inflation often overshoots the devaluation itself.

In addition, the government’s budget deficit has been increasing rapidly. In the first 11 months of the 2015-2016 fiscal year (the most recent data available) the deficit exceeded LE311 billion, or 11.2% of GDP, well above the 8.9% projected at the start of the year. For the 2016-2017 fiscal year, the government plans a deficit of LE319 billion, or 9.8% of projected GDP. As such, the government is constantly contemplating the introduction of additional taxes – currently, plans to impose a Value-Added Tax (VAT), which would likely range between 12 and 14% on a number of consumption goods, is under discussion in parliament. While the government may need the tax revenue, raising prices is going to further hurt Egyptian consumers.

The import-export balance also keeps severely declining. The balance of payment recorded a gap in the second half of 2015 of $3.4 billion, compared to $1 billion in the same period a year prior—a frightening 240% growth. The current account deficit more than doubled, from $4.3 billion to $8.9 billion over the same period. Tourism revenue declined by a third; Suez Canal proceeds declined by 7%; export proceeds declined by more than a quarter (though the latter was more than offset by the decline in the import bill, thanks to the decline of oil prices). Though foreign direct investment rose by 20%, capital markets remain weak, leading many Egyptians to park their funds in safer locations. This flight of capital also exacerbates the currency problem.

This is best illustrated by a report by the Dubai Land Authority published this week and widely debated in Egypt, which showed that Egyptians were the second largest non-Gulf Arab buyers of real-estate in Dubai in the first half of 2016, investing 1.4 billion Emirati dirhams ($381 million)—a 40% increase compared to 2014. That these non-productive investment would go to a market that may itself be exhibiting signs of a bubble is not very surprising; many Egyptians, after all, are seeking to put their money in what is perceived as a safe location, rather than to take advantage of investment opportunities. These particular investments are not causing the crisis, but they are symptomatic of an increasing outward movement of capital that is putting additional pressure on the value of the pound.

An official devaluation is inevitable. There is simply too much pressure, from the weakening economy, the demand of businesses, individuals, and speculators, for the status quo to persist. The amount of this devaluation will depend on the CBE’s estimates of the real exchange rate, disregarding the temporary panic and speculation. While the CBE is hoping to choose a time to limit the inflationary effect of the devaluation, it is clear that additional delays will only exacerbate the problem.