Developed for Global Nation, this new report surveys the Climate & Health ecosystem and presents ten case studies of interventions and strategies from around of the world, offering fresh ideas and highlighting projects worthy of replication.

We have excellent content for you this week!

We were happy to ‘sit’ with the Talking Africa podcast for a conversation about the economic situation in North Africa, the COVID-19 response of regional countries, debt relief on the continent, among other topics.

Please listen and share your comments!

ALSO please check this CNBC op-ed, “Africa needs to work together, with all sectors of society to deal with COVID-19” penned by the Africa Unusual Working Group, which we cofounded.

IN ADDITION, view the recorded conversation we led over at Chatham House, with David Butter, about his latest policy brief on Egypt and the Gulf: Allies and Rivals.

OXCON is happy to present our latest policy paper, on economic cooperation in North Africa, co-authored with the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, which builds on a series of roundtables organised by Chatham House across the region over the past 14 months. We hope this kickstart fresh discussions on the possibilities, and limitations, of the discourse on ‘regional integration’: perhaps it’s better refocused as a search for synergies, building blocks towards improved cooperation, rather than setting ‘integration’ as an unattainable goal.

You can read it online, or download a printable version in English and in Arabic. Happy reading!

Discussions of North African integration have evoked ideas of a shared identity and a common destiny in the region. However, recent attempts to build regional blocs in North Africa have been unsuccessful. This paper examines the benefits of a ‘synergistic’ approach to North African cooperation.

Summary

OXCON is glad to partner once again with the Africa Impact Investing Leaders Forum. This year, we had the opportunity to address the audience of the AIILF on such topics as investment in LDCs and fragile countries, the role of DFIs, the potential of creating national and regional Guarantee funds, and how to utilise existing investment structures to achieve the SDGs.

The year got to a raging start and we’ve had scant time to update you on our public engagements!

But we’ve been immensely fortunate to interact with a wide range of partners and clients, and address very diverse audiences around the world over the past few months.

To give you the highlights,

In March, we addressed the OXFAM West Africa regional workshop on “Youth Employment in Value Chains in West Africa” in Niamey, Niger; introducing participants to the concept and implementation of value chains, notably at the bottom of the pyramid.

We spoke at the University of Oxford’s Africa Business Forum. Organised under the topic of “Single Market, Global Outcomes”, we spoke at a panel titled “Rebooting the sleeping giant: The fundamental infrastructure, energy and policies needed to support integrated trade across Africa”.

OXCON also contributed to the Commonwealth Africa Summit 2019. Under the theme “Investing in our Common Future”, we contributed to two different panels – “Doing Business in Africa: Managing the Corruption Factor” (alongside Peter Eigen, a personal hero of ours), as well as on “Fostering innovation in Commonwealth Africa to meet the continent’s unique challenges”.

In January for instance, we were graciously invited to attend, and address the Raisina Dialogue, India’s premier public policy conference. The panel, on the progress of gender equality on year after the ‘#MeToo’ movement, benefited from a number of perspectives from around the world.

The end of last year was also quite busy from a public engagement perspective. In December we got to enjoy the sun (but not the fog) of Morocco, where we addressed the audience of the Atlantic Dialogues in Marrakech, on “Fighting Corruption: Can Civil Society Lead the Way?”; as well as join a Chatham House expert round-table in Rabat, on “New models for transformation and cooperation for North African Cooperation and Competitiveness”; a few days before that, we joined the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA)’s Annual Democracy Forum in Windhoek, Namibia, addressing the audience on “Technology and Inclusion in Democratic Processes”.

Maxime Weigert and Mohamed El Dahshan look at the promise and potential of regional value chain development on the African continent, offering remarks and suggestions on how to best take advantage of the RVC approach in light of global developments.

Originally published in Yale Global, 26 February 2019

LONDON: While some observers look at Africa as the next factory of the world for labor-intensive manufacturing activities, African nations may find more success by pursuing regional rather than global value chains.

The concept of regional value chains, increasingly perceived as a viable alternative to the paradigm of global value chains, has long dominated the thinking of international institutions as a primary model for Africa’s industrialization. Indeed, the African Union sponsored African Industrialisation Week in December and focused on regional value chains in the pharmaceutical industry as the theme.

With Africa’s industrialization a priority, development finance institutions promote export-oriented diversification and inclusive and job-generating growth on the continent. A common narrative is Africa pursuing more manufacturing activities as wages rise in China. This scenario promises linking Africa into dynamic global value chains connected to more developed world markets, including China.

Attempting to duplicate China’s industrial experience in Africa as a whole is questionable, even if one sets aside the numerous historical, economic, political, institutional, sociocultural and geographic differences distinguishing the two places. Any such attempt poses two major risks:

● First, African countries are likely to attract low value-added manufacturing activities with low labor costs, requiring unskilled workers as the main production factor. The stage, though probably inevitable, could unleash competitive pressures among countries and result in a race-to-the-bottom on social and labor regulations. The lowest bidder would take all in such a game – especially considering that most countries do not offer lower labor costs than China. The strategy might promote divisiveness on the continent, precisely at a time when African governments are seeking to improve cooperation and deepen regional integration, developing a united front.

● The second risk is less immediately tangible. China started to industrialize during the 1970s, but today’s global industrial outlook is characterized by greater uncertainty. In the medium-term, factory automation and other labor-saving technologies could lead to the disappearance of many manufacturing jobs, particularly lower-skilled ones. For countries hoping to attract labor-intensive activities, this might result in a “premature deindustrialization” for any undertaking the early steps of the industrialization scale. Whereas developed nations, as well as rising powers like China are already designing the future of manufacturing, latecomers such as African countries may not want to rush into a model rapidly becoming obsolete. The same applies to the energy that these industries would consume, with a noticeable – and worrisome – growing appetite for coal-powered plants, many of which are funded by China.

Regional value chains offer a response to both risks. These regional variants of global value chains can be viewed as production systems from input provision to commercialization, spread beyond national borders to exploit existing complementary activities within a region, such as differentiated labor costs and productive capabilities, natural resources or geopolitical features that include maritime access, trade agreements with extra-regional partners and more.

Broadly, target countries can pursue two models of regional value chains, whether they are outward looking and supply global markets or are inward looking with development intended for regional consumption markets.

The first is export-oriented and occurs when countries in the same region combine forces, organizing regional division of labor, collectively strengthening their position to climb a specific global value chain as a regional block. This requires them to coordinate incentives, intra-regional trade agreements, services promotion and shared infrastructure development, to support sector and channel trade as well as investments with extra-regional partners. A typical example of such activity is the integration of ASEAN manufacturers into the electronics global value chain, led by Japan, China and the Asian Dragons. While government support is critical for establishment of regional value chains, these are mainly exogenously-driven by multinational companies’ outsourcing investments. Countries must foster strong ties with multinationals, convincing them to locate massive upstream value chain activities, including raw materials, components and spare parts, and build the required industrial fabric in the region. This is why such regional value chains present limited, albeit promising, opportunities in Africa – for example, the automotive sector in North Africa and the clothing sector in Southern Africa.

The second model focuses on import-substitution – but at the regional scale, offering fresh breath to a classic idea, while avoiding the pitfalls of yesteryear. Import-substitution strategies in the 1970s suffered from small markets and dominance of publicly owned companies. More than 40 years later though, markets are already larger – but more importantly, regional markets, beyond national boundaries, are already established with strong private-sector presence.

Import-substitution regional value chains consider products both produced and consumed within the same region, creating potential complementarities, merging production capabilities with consumption potential. This type of regional value chain has the advantage of being intraregional and, as such, does not face barriers to entry, such as Brazilian soybean or Chilean salmon, largely processed and consumed within Latin America. Even more so, these regional chains are somewhat protected from foreign competition, allowing for gradual development. Furthermore, by focusing on regional sales, these chains do not face the intense and, at times, nakedly superfluous standardization and quality norms and constraints imposed by developed export markets.

Regional value chains are particularly well suited to serve regional tastes and cultural preferences. The food industry offers the clearest example. A number of food crops across the continent produced and consumed regionally such as yam, cassava, potatoes and aquaculture products are hardly subject to international competition – in part due to their perishability – and could thus be developed and grown thanks to regional chains, protected in part by local tastes and dietary habits. This regional model is applicable to other industries where idiosyncratic factors determine consumption behaviors and market opportunities, including pharmaceuticals and tourism.

In many ways, regional value chains are hardly a novelty and already exist on the continent – just without the formal label – including the tea industry in East Africa, livestock between the Sahel and Gulf of Guinea, or cassava in West Africa. Such chains present an opportunity, a starting point several steps ahead, to industrialize these streams of goods and add value to the products. As regional value chains emerge, the more they will organically develop, especially considering unstoppable regional trends of growth, consumption and industrialization. The process requires both state-led integration and private sector participation.

Africa’s private sector firms are the best placed to take on the task of leading the development of regional value chains, thanks to their established presence. They bring hosting experience and ability to navigate their local markets and business environment, both in terms of financing and value creation, making them competitive in local and regional spheres. Nonetheless, these firms face a multitude of challenges – including access to credit, persistently narrow domestic markets, high production costs and low technology appropriation. The benefits offset their technical frailty as innovation for regional value chains will be organizational and operational rather than technological. Such constraint-based innovation allows them to tap into the sizable bottom-of-the-pyramid markets across the continent. To lead on these regional value chains, African governments and their private sectors must pursue new relationships.

In cooperation with the Observer Research Foundation, India’s foremost public policy think tank, OXCON is delighted to share this article, presenting some of our thoughts on the reconstruction process of Kerala following the severe flooding it has endured over the past month.

The torrential rains and the ensuing floods in the southern Indian State of Kerala have led to one of the largest humanitarian crisis of the year, with more than 470 people killed and upwards of 700,000 displaced.

As the humanitarian relief is ongoing, it is crucial to also consider the long-term reconstruction effort that will need to come swiftly on the tails, if not concurrently, to the humanitarian intervention. The crisis mustn’t be allowed to hamper Kerala’s impressive social and economic development. If anything, the reconstruction process should be geared towards allowing for better means of growth, developing the physical, institutional and human infrastructure to facilitate achieving long-term goals.” As the Member of Parliament of Kerala’s capital Thiruvananthapuram, Shashi Tharoor, suggested, five ‘R’s need to be addressed — rescue, relief, risk, rehabilitation and rebuilding. But humanitarian and reconstruction interventions mustn’t be thought of independently, but rather as a continuum aiming to “rebuild Kerala better.”

Such a process should thus look beyond reconstruction the way things were, but to build according to where we want to go. The first step would be to study past experiences around the world and avoid common mistakes that would curtail Kerala’s path to development, while closely studying the situation on the ground before and after the floods, to devise key recommendations.

From relief to development, some actions may be sequential and stand to be developed in isolation; but in most cases the reconstruction and development must be planned, and in some cases implemented, from the onset of the relief effort. Planning and costing often needs to be done in tandem; keeping the interest of people, both on the short and long-term, as the guiding principle.

Natural disaster relief will seek to move people from displaced camps to temporary housing while the reconstruction is ongoing; this is a laudable effort, as camp conditions are difficult, particularly in a monsoon season, and it is imperative to lead people to safety so that they may reestablish a semblance of normalcy. But many a relief effort around the world, such as that following the 2004 tsunami, saw temporary housing construction projects go far over budget — often simply for failure to take into account the price increase of construction material that comes with a spike in demand — which impeded ability to develop adequate long-term housing for returnees.

Planning and costing often needs to be done in tandem; keeping the interest of people, both on the short and long-term, as the guiding principle.

Pressured by time and the need for quick delivery, many a post-disaster reconstruction situation end up seeking to replicate things the way they were before. But a massive reconstruction phase affords a unique opportunity for important investment across multiple sectors, and good policymakers will seek to take advantage of this to upgrade their economic and social infrastructure, thus avoiding replicating the structural weaknesses that were present (and which might have effectively contributed to the crisis itself) but also creating something worthy of the hopes and aspiration of the State and its people, by improving their living conditions and the services they have access to.

Take infrastructure, for instance. Beyond the human impact, the most noticeable and visible impact of flooding and landslides is on infrastructure — which includes roads and bridges, but also electricity and fuel supply, water and sanitation, rail, ports and airports, telecommunications, educational and medical facilities, and so on — in addition naturally to housing, which, by virtue of its private ownership, is usually addressed separately.

Floods are estimated to have destroyed or damaged 83,000 km of roads, including 16,000 km of major roads (known as PWD — Public Works Department roads, as opposed to the LSG — Local Self Government roads. Repairing those must also include an upgrade — both of the roads quality, which leaves much to be desired, as well as of the road grid itself, potentially taking the opportunity to extend PWD roads inland. Highways in Kerala are known to be narrower than the rest of the country; this is an opportunity to improve them.

For some transportation but even more so for service infrastructure, the state may wish to consider public-private partnerships, set up in cooperation with private sector operators. Take energy for instance. Kerala generates three quarters of its energy from hydropower, a sector very apt for PPP engagements. Kerala could stand to increase its hydropower generation, notably in small and distributed projects (up to 10 MW). Those agreements typically involve the private sector designing, constructing, operating, maintaining and managing hydro-electric facilities, which would allow rapid scaling across the state. Investment guarantees could be provided by international donors.

It is likely that sufficient funds would not be available to fully finance such needs. Prioritisation is of course necessary. But in no way does this take away from the necessity of planning long-term. When developing short and medium term targets, future goals must be taken into account when designing interventions; infrastructure must be designed to be scalable and connectable. A good example is the modular development of the much-hailed Kochi Metro project; plans for the three phases were developed from the onset, with latter phases added subsequently.

When developing short and medium term targets, future goals must be taken into account when designing interventions; infrastructure must be designed to be scalable and connectable.

The crisis has brought out the best in the people of Kerala, with people across religious and caste divides operating seamlessly together to alleviate the suffering of their compatriots. Even between Keralites and residents from other states, primarily the country’s north east, who have moved en masse into the state’s urban centres to take up blue collar jobs. It is operative that the reconstruction and development process capitalise on this spirit and expertise, to foster a feeling of inclusivity during and after the process. It will also cement one of Kerala’s strongest attributes — the relative lack of religious and caste barriers between groups — and prevent extremist groups, such as the Popular Front of India (PFI) or the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) from scoring political points and making inroads among distressed people in their usual divisive rhetoric, by stoking divisions or perceived favouritism on the part of the authorities.

Involving Keralites throughout the process will also allow to better sensibilise them to the kind of response and mitigation necessary, acting as a practical educational tool in integrating sustainability and risk reduction and mitigation in people’s daily activities.

While economic activity has largely ground to a halt in many areas of the state, it is necessary to develop distinct sectoral approaches, and identify which sectors would have been hit the hardest. Some might have suffered particularly severe shocks that would derail them or permanently push a segment of their workforce out of their jobs, making their economic recovery particularly tortuous.

Agriculture is on. The waters are estimated to have submerged 40,000 hectares of land, and damaged crops in their peak harvest season. In addition, the flooding would have caused degradation of agricultural land, thus hurting farmers not only this year — but also the next. A risk in such cases would be that farmers would move away en masse from agriculture to pursue other economic activities, abandoning their farms and hurting future agricultural production and exports. Land rehabilitation and agricultural support will thus need to be a priority.

Tourism as well, accounting for 12% of the state’s economic activity and 20% of its employment, will also have taken a particularly strong hit. The damaged infrastructure and difficulty of access have led to more than three quarters of reservations cancelled for September; October, the peak tourism season, is likely to see a 20 to 25% drop.

While economic activity has largely ground to a halt in many areas of the state, it is necessary to develop distinct sectoral approaches, and identify which sectors would have been hit the hardest.

Another example is the retail sector. Onam, the Hindu festival celebrating the harvest, would have fallen in the second half of August this year — but it was, unsurprisingly, swept with the floods. But more than a religious occasion, Onam is also the yearly peak shopping season for everything from durables to perishables, from cars and furniture to flowers and pickles. A failed Onam retail season means that retail across the state would have globally taken a severe hit that will affect many businesses bottom lines, losses which they could struggle to make up — adding additional strain.

It’s a clear pattern: donations and aid will come in at the peak of global interest in a crisis, and very rapidly decline as global eyeballs turn elsewhere, just as the reconstruction and development picks up, along with its spending needs. To control disbursement it will be necessary to ensure that the Kerala government is in the driver’s seat, rather than donors; though thanks to strong institutions at the national and state levels, this is unlikely to be a challenge. Nonetheless, securing the necessary funding will, particularly past the emergency phase.

Calling for a UN meeting on Kerala Reconstruction is unlikely to yield the required results. For one, there is a distinct fatigue of such reconstruction international conference, even for countries in a significantly worse situation. To give a stark recent example, the latest fundraising conference for Syria, which aimed at raising USD 9 billion for refugee needs, only obtained USD 4 billion — two of which having already been pledged before the conference.

To control disbursement it will be necessary to ensure that the Kerala government is in the driver’s seat, rather than donors.

Instead, Kerala could develop a clear Reconstruction and Development Plan listing its project and spending priorities, which it should share widely and bring onto the public scene, and engage in a series of bilateral negotiations with intergovernmental and national donors to secure funding for its various priorities. Naturally the government of India should be the leading actor for this purpose.

The reconstruction process must consider both existing, but also future environmental needs. Unfortunately, we must consider the possible repetition of such events, with the torrential rains that Kerala has received only part of a pattern of increasingly violent natural disasters cause by unstoppable climate change. Models will therefore need to be developed to estimate the future occurrence of such natural disasters, and reconstruction will have to internalize those projections.

And evidence is already pointing out that Kerala is already falling behind. Not a single one of Kerala’s 61 dams had an Emergency Action Plan or an Operation & Maintenance (O&M) manual on how to manage an extreme event such as flooding, and “no dam-break analysis was conducted in respect to any of the 61 dams in the State,” as per a 2017 report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India.

Experts are pointing out that the impact of the floods could have been mitigated if prior environmental assessments had not been ignored. The Western Ghats, which have traditionally served as a water reservoir for Kerala along with five other States, were the subject of a 2010 environmental protection assessment report, which recommended a ban on mining and stone quarrying, and limited various economic activities in the Ghats. The report was not implemented and subsequently watered down, and this excessive stone quarrying and deforestation of catchment areas may have contributed to the scale of flooding and destruction this month.

An urgent reversal of the trend is crucial — not only for disaster prevention, but also for economic and human sustainability.

The Western Ghats, which have traditionally served as a water reservoir for Kerala along with five other States, were the subject of a 2010 environmental protection assessment report, which recommended a ban on mining and stone quarrying, and limited various economic activities in the Ghats.

Kerala’s water resources are already under threat. Its 44 rivers have greatly suffered from unsustainable industrial activity. In addition to pollution caused by the dumping of solid waste and the discharge of industrial effluents, rivers also suffer from unsustainable sand mining, to answer a demand in construction. The removal of sand causes riverbeds to sink, threatening not only the rivers themselves but also ponds they feed into and groundwater they replenish.

Groundwater, which provides 50% of agricultural irrigation and supplies 80% of rural and 50% of urban households with their domestic needs, has not escaped unsustainable practices either. The State has the highest open well density in all of India — up to 200 wells per square kilometre in coastal areas. Groundwater, has witnessed a decline in quality due to contamination and seawater intrusion.

Deforestation and soil pollution also follow similar patterns of unsustainable human usage, from illegal encroachment on forests to extreme use of pesticides.

All of these concerns must be taken into account when designing long-term development plans; reconstruction must ensure that it is done at the expense of the health of the region’s trees and rivers, that quarrying and clay mining activities do not exceed acceptable limits nor represent a pollution risk to the health of citizens.

The reconstruction is bound to be a long and costly process. Thankfully, the people of Kerala have proven that they are stronger than any adversity. It is important for good policy to be developed, which will increase future readiness, taking into account projections of similar disasters, while concurrently upgrading the services and infrastructure to increase the quality of life of every Keralite.

Photo credits: Press Trust of India

Nairobi, Kenya –

How should policy researchers and consultants communicate with governments – and how is it different in autocratic regimes?

The genesis of this reflection came on the back of discussions at the “African Evidence Informed Policy Forum in Nairobi – a gathering of researchers, academics, think tanks, and foundations attempting to encourage and advance the practice of developing evidence-backed policy in Africa, and which OXCON was invited to.

Which may seem like an obvious goal – but evidence (ha!) proves it often isn’t.

And one recurrent topic – arguably not a novel but a perennial one – was the engagement with the government on developing those policy recommendations – particularly challenging governments.

On one corner are those who believe that the research process should be developed in full isolation from the State, under the banner of “academic neutrality”; in the other are those who believe that involving the end recipient in every step of the work being developed in the best way to ensure its acceptance and usability.

For us, it is painfully clear that a ‘first-best’ policy that is not political feasible, is not first best.

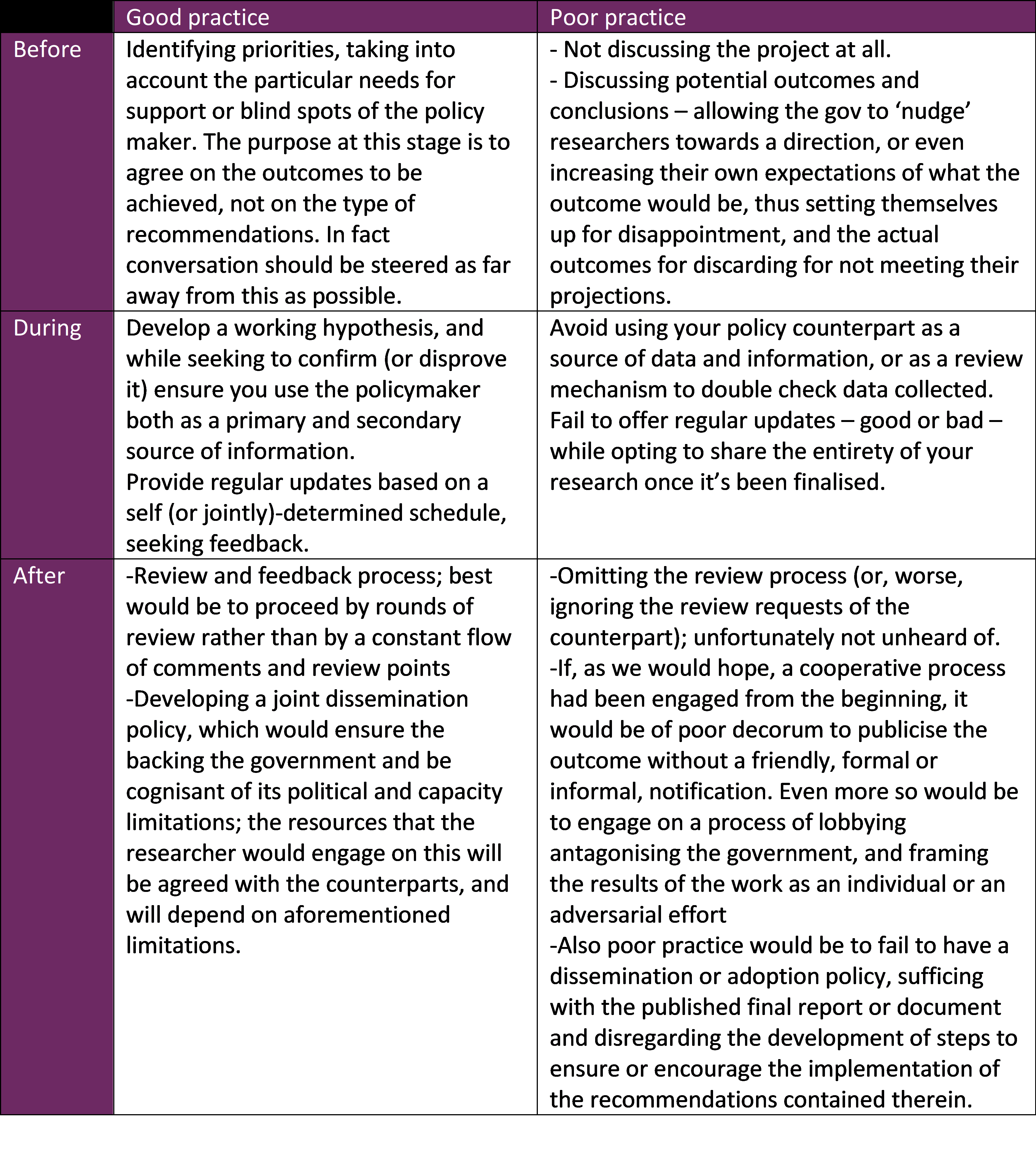

There are three distinct connection points for engaging with the policy players:

First, before the project: failing to cooperate with the recipient of your work is a sure way of maximizing both the chances of inadequacy, inappropriateness, and of rejection of the policy recommendations. Properly tailoring and calibrating the work to the recipient’s needs and limitations provides a much greater chance for applicability.

Second, during the project: regular touch points are key, particularly in the earlier stages of the engagement. The consultant needs at this stage to have developed a working hypothesis to be tested; the progress there would be shared regularly with the counterparts, as they would act as an important resource – both for primary information collection, but also to check assumptions.

Sharing partial conclusions, possibly according to a self or jointly-determined schedule, is also an excellent practice that unfortunately too many researchers seem to ignore.

Third, following project completion: rounds of review – largely to the discretion of the policymakers but generally within an agreed timeframe –

To break it down further, and to compare good from poor practice –

Policy Advisory on/in Autocratic regimes

Naturally, context matters. Whereas some governments would be open to hearing different ideas and accepting – even begrudgingly – criticism, others are altogether unwilling to entertain any thoughts that would represent divergent thinking to their own. Working with such unfriendly governments entails a different modus operandi. A researcher would likely be engaged in a development policy formulation and strategizing effort on behalf of an outside institution, likely an international organisation; but disengaging altogether from the local policy actors would nonetheless be a mistake.

As we are primarily concerned with the policy recommendations to be implemented, ensuring a certain level of buy-in would be important, as ex-post lobbying is likely moot; thus, early conversations would be necessary to explain the purpose of the work as being to improve the work of government, which it is, rather than an adversarial process, which would threaten the value of the research – and in some contexts, possibly the researcher herself.

Communication during the research process itself will likely be limited; save for potential friendly officials who may be willing to provide data – though experience proves this is often a far stretch –

After the recommendations have been finalised, it would be judicious to communicate results privately with the government, if such a pathway is open; if not, publicising it as a recommendation – while, naturally, highlighting and acknowledging the support and leadership and so on of the leading government figure – a safety mechanism.

Wrong incentives

One final issue of relevance, and which warrants additional reflection, is what incentives governments provide for developing the very evidence they should be building their policy analysis and strategizing on. One glaring example, for instance, was the case a Tanzanian government officials who was prosecuted, under the restrictive 2015 Statistical Act of Tanzania, for releasing figures that contradicted official ones.

Government actions, be they in their regulations or in practice, can put a chilling effect on public policy research, regardless of any collaborative attitude the researchers’ counterpart may display.

OXCON’s Amina El Abed pens an analysis exclusively for Yale’s Global Review, on the determinants of Tunisian foreign policy, and the urgent need for the country to develop coherent messaging across all institutions that express positions on regional and global issues, occasionally at violent odds with the state’s official positions.

Read more: The Making of Tunisian Foreign Policy

“Busan, South Korea” in Wakandan script – screenshot from Black Panther (2018)

OXCON is delighted to be in Busan, Korea, home of one of only five megaports in the world – as well as that incredible car chase scene in Black Panther – for the African Development Bank’s Annual meetings, upon exclusive invitation of the AfDB.