Nairobi, Kenya –

How should policy researchers and consultants communicate with governments – and how is it different in autocratic regimes?

The genesis of this reflection came on the back of discussions at the “African Evidence Informed Policy Forum in Nairobi – a gathering of researchers, academics, think tanks, and foundations attempting to encourage and advance the practice of developing evidence-backed policy in Africa, and which OXCON was invited to.

Which may seem like an obvious goal – but evidence (ha!) proves it often isn’t.

And one recurrent topic – arguably not a novel but a perennial one – was the engagement with the government on developing those policy recommendations – particularly challenging governments.

On one corner are those who believe that the research process should be developed in full isolation from the State, under the banner of “academic neutrality”; in the other are those who believe that involving the end recipient in every step of the work being developed in the best way to ensure its acceptance and usability.

For us, it is painfully clear that a ‘first-best’ policy that is not political feasible, is not first best.

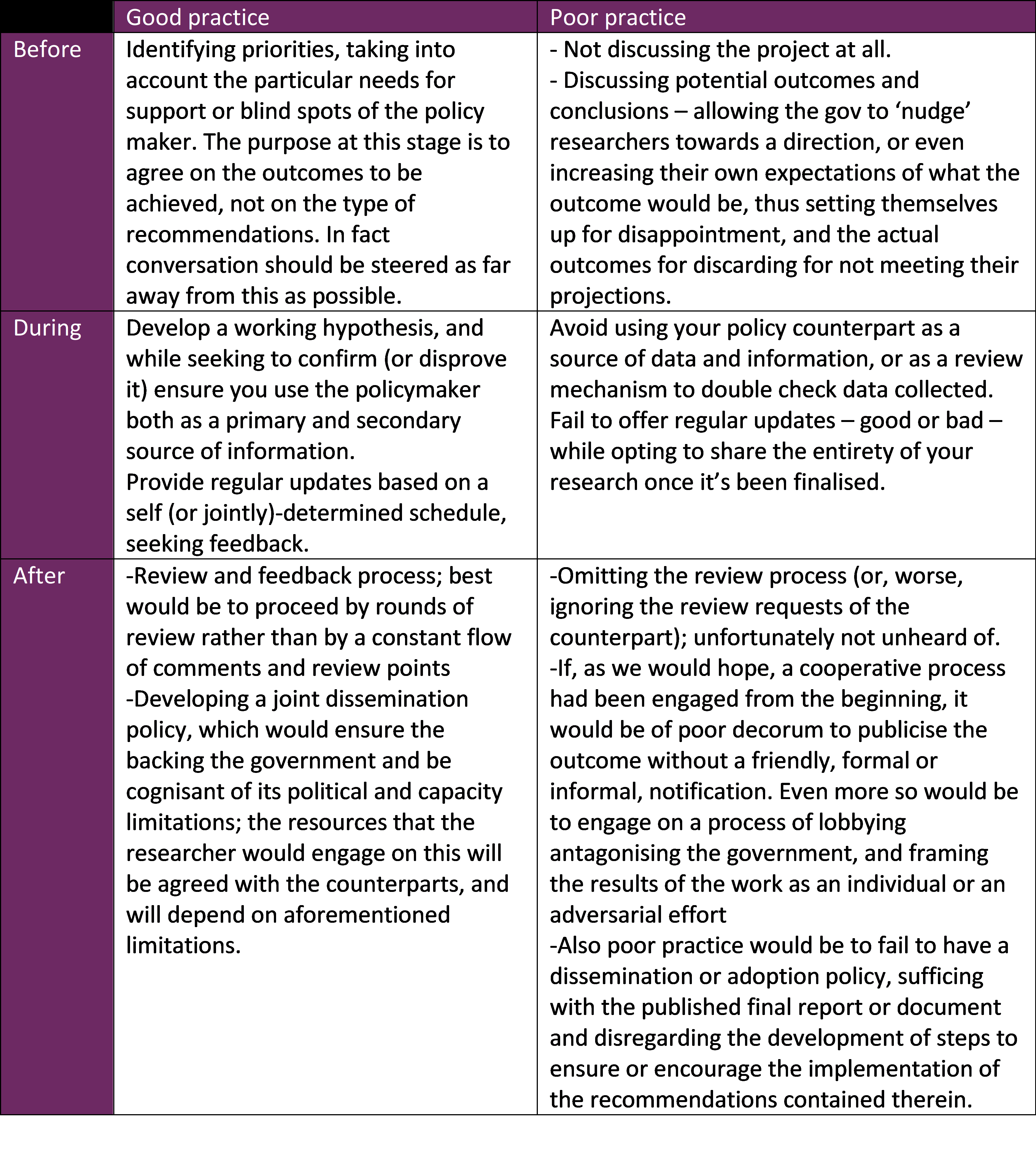

There are three distinct connection points for engaging with the policy players:

First, before the project: failing to cooperate with the recipient of your work is a sure way of maximizing both the chances of inadequacy, inappropriateness, and of rejection of the policy recommendations. Properly tailoring and calibrating the work to the recipient’s needs and limitations provides a much greater chance for applicability.

Second, during the project: regular touch points are key, particularly in the earlier stages of the engagement. The consultant needs at this stage to have developed a working hypothesis to be tested; the progress there would be shared regularly with the counterparts, as they would act as an important resource – both for primary information collection, but also to check assumptions.

Sharing partial conclusions, possibly according to a self or jointly-determined schedule, is also an excellent practice that unfortunately too many researchers seem to ignore.

Third, following project completion: rounds of review – largely to the discretion of the policymakers but generally within an agreed timeframe –

To break it down further, and to compare good from poor practice –

Policy Advisory on/in Autocratic regimes

Naturally, context matters. Whereas some governments would be open to hearing different ideas and accepting – even begrudgingly – criticism, others are altogether unwilling to entertain any thoughts that would represent divergent thinking to their own. Working with such unfriendly governments entails a different modus operandi. A researcher would likely be engaged in a development policy formulation and strategizing effort on behalf of an outside institution, likely an international organisation; but disengaging altogether from the local policy actors would nonetheless be a mistake.

As we are primarily concerned with the policy recommendations to be implemented, ensuring a certain level of buy-in would be important, as ex-post lobbying is likely moot; thus, early conversations would be necessary to explain the purpose of the work as being to improve the work of government, which it is, rather than an adversarial process, which would threaten the value of the research – and in some contexts, possibly the researcher herself.

Communication during the research process itself will likely be limited; save for potential friendly officials who may be willing to provide data – though experience proves this is often a far stretch –

After the recommendations have been finalised, it would be judicious to communicate results privately with the government, if such a pathway is open; if not, publicising it as a recommendation – while, naturally, highlighting and acknowledging the support and leadership and so on of the leading government figure – a safety mechanism.

Wrong incentives

One final issue of relevance, and which warrants additional reflection, is what incentives governments provide for developing the very evidence they should be building their policy analysis and strategizing on. One glaring example, for instance, was the case a Tanzanian government officials who was prosecuted, under the restrictive 2015 Statistical Act of Tanzania, for releasing figures that contradicted official ones.

Government actions, be they in their regulations or in practice, can put a chilling effect on public policy research, regardless of any collaborative attitude the researchers’ counterpart may display.